Recreating the town of Scarborough, Yorkshire: Post 2: Shaping the Town, Quodlibet 1264

Medieval Scarborough is not just a dream. It, and the people who lived and died there, were real.

Some stories wind all over the place and do just fine without the need to catch the essence of a place. I am cursed with the need to overthink things, and in doing so, sometimes I find the story takes on its own life. Google cannot help you find medieval Scarborough - there is too much guesswork involved. Until we get the time machine pointed back in the right direction, the best we can do is to build something based on the little we know. Please remember, if you are seeking historical truth rather than my interpretation of it, please check out the Scarborough Archeological and Historical Society.

How many?

We are interested in the year 1264CE. No one knows, but a fair guess might be that there were about 250 households. If each were occupied by 4.5 people, we would have a town population of 1,125. Allowing a spread across the age groups tapering at age 70, we guesstimate 200 small children, 230 young people, 395 younger adults, 270 older adults, and 30 elderly folks. Not all guess-work: medieval child mortality was 25% in the first year with only 2/3rd surviving to adulthood. Maternal death rates were 13 per 1000 live births. We can assume a higher than normal rate of adult death through misadventure or the dangerous activities of adults. Balancing this, against the odds, this was also a period of relatively good health: free from plague, the scourge of overpopulation, and poor nutrition.

One hundred years earlier, the Oldborough had threatened to burst its seams - at least, sheep flocks and industry could no longer be safely confined within the wall, and so Newborough was tacked on to the west. Despite rosy predictions, Newborough, centuries later still remained sparsely populated. Well, apart from the sheep and a couple of growing monastic communities. Overseas, the crusader kingdoms of the Middle East were in decline. The Byzantine Empire had retaken Constantinople and the militant monastic orders that had served as a basis for control of the regions were limping home (or, at least, back to a safer location). Many monks had lived their entire lives overseas and many suffered from injury and privation. The monastic orders were swelled by these refugees - who, for a while, threatened to swamp local towns.

High above both of the towns, the castle population waxed and waned depending on royal patronage. We actually have some earlier numbers here... "In 1202 and 1204 John de Builly was the constable, and then and in 1213 military prisoners were kept there. In 1208 Builly was superseded by Robert de Vaux, and he again in 1215 by Geoffrey de Neville, the King’s Chamberlain, at which time sixty “servientes” and ten “balistarii” seem to have constituted the garrison." By 1264 the timbers of King John's buildings were in sore need of repair.

Further from town, nearby private manors and hides (smaller farmsteads of 120 acres split into 4 households), and smaller towns were still recovering from the invasion and the subsequent drain of skilled workers to the crusades and larger centers.

Peter Corless, a games designer, once did some sampling from the Doomsday material. His research suggested that, in a reasonably wealthy area like Scarborough, for a population of about 1000, we might expect 500 oxen (for plowing/carting), 50 head of cattle (milk, butter, cheese, and meat), 8 horses (cartage, transport, communication), 50 goats (milk and meat), 135 pigs (meat), and 890 sheep (meat and wool). To this, we will add 1,000 chickens and ducks (eggs and meat) and a flock of ravens. Houses kept dogs, cats, and rats as pets.

Wood and Stone

Town building is tough work requiring lots of wood and stone.

The Crown granted 40 mature oaks to the town each year. Forestry operations have not changed much over the centuries. The fallen trees were dragged downhill to the nearest road where heavy wagon trains brought the timber to town. In living memory, the great forests of the wilderness I live in, near the alps of New South Wales, were cut down, milled and transported 30 miles over rough hilly roads to the nearest town - with little more than horse and oxen power.

In 1264, this may have amounted to about 100 tons of useable oak or a yield of 15,000m of 2" by 4" planks and 7,000m of 1" by 12" boards. Operations took oak trees (Quercus Petraea and Robur ?), probably by way of pollarding (pruning heavy branches well off the ground to stimulate growth). Pollarding operations maximize nearby pasture land for town use and provide good fodder.

This may seem like an over-sufficiency of wood, but it probably remained scarce (and, in 1264, King John's additions to the castle were in poor repair). While a small one-person riverine fish boat might make do with 10m of boards, a small coastal boat requires 400m boards and an ocean-going vessel might exceed 2000m boards. A house could use 200m of boards and 400m of planks, a bridge or bridge repair might take 200m of boards while a large warehouse might consume 12,000m of boards. The availability of timber was a significant limit on the number of large new projects each year.

Domestic heating and cooking relied on wind-gifts from the forest. Wood-rows would have been a feature of every building - and a cause of continual effort.

Stone was taken from nearby bays. Milled into crude blocks on site, the raw material was then carried by barge across the bay to be used to construct the harbor wall and stone footings for houses. This would have been a slow and dangerous operation. Milled stone can probably be found on the bottom of the bay. Smaller stone tiles were cut from nearby valleys.

On land, most of the heavy lifting was done by teams of ox. In confined places, cranes driven by people-power or systems of rope would have been used.

Outside a rural setting, 500 ox seems an impossibly high number - which would beggar the town's pastures for no apparent purpose. I am inclined to discount this number in a town environment. My great grandfather was one of the last to use teams of oxen for this purpose in outback New South Wales, for earthworks, road, and dam building. After WWI, oxen teams gradually disappeared, initially replaced by teams of horses (and the occasional steam-powered mill) and then the infernal combustion engine.

Providing rural services over a wide farming area, kept three teams of oxen until his death between the interwar period with about 20 beasts at any one time.

I still have the yoking rigs he used, heavy leather outers packed around an inner shaped piece of pig iron - in those days, an expensive kit. In medieval farming areas, I think it is more likely that one team (plus a couple of spares) was kept in rural areas per hide (a group of 4 households on about 120 acres). In a town, 10 teams (80-100 oxen) would have more than sufficed - and many of these would have been involved in forestry work and cartage. They would have converged for plowing and heavy work when the town yoked them into teams of 8 to plow the 1000 acres or so of hard clay soil for grain farming. Apart from this, oxen were used for land leveling and the movement of everything else from trade goods, timber, harvest, rocks, stone, and soil.

Heavy wagons could not enter town across the moats and wooden structures spanning the Damyot. So, we have placed a timber yard outside the Newtown gates. Timber would have been broken up there into forks, building boards or planks and carried to carpenters inside the town enclosures - and because of the limited egress into the Oldborough at this stage, there may have been carpentry shops in both Boroughs. I assume that house frames (particularly 'fork-frames') were constructed 'off-site' and brought to a building site only after stone footings had been completed (perhaps this was a balance-of-convenience calculation).

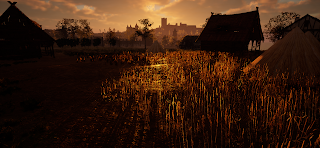

Off-set housing construction site, Quodlibet

Flocks

While sheep were held by individual owners, they were pastured as a single group with 1 shepherd per 5 sheep during the day (the control of grazing was a key concern to prevent the destruction of crops).

In 1264, wolves still roamed the forest. Assuming that older children and elders took this task on, this would have kept about 2/3rd of them out of mischief. On the edge of the medieval town is a location called Huntriss Row. The names of places and lanes in the town hint at past activities. Perhaps this is an echo of adult women taking turns protecting the flocks and the child escort from danger from the nearby forest. In that enlightened age, the pernicious sport of cricket was prohibited in England, and each child was commanded to learn to shoot the long bow. No hand-held computers or phones are found in the archeological record.

Goats were farmed for milk and meat and, because goats are by nature wicked, they were carefully tethered. Pigs were intensively farmed with 2 litters a year for meat. Because of the propensity for good-natured damage pigs were nose-ringed and kept close to home. Both pigs and goats have a well deserved reputation for escaping confinement and causing damage to crops (one of these trespassing animals could be killed on sight - a legal rule that has only disappeared in living memory) - and the rolls of the town court would have been full of fines for damage.

Animals were slaughtered outside town, near water, and taken into town for sale. Nothing was wasted. Excess meat was preserved in salt. Bone was used for transparent window openings and as a plastic precursor. Hides were preserved and converted into leather and used for tools, harnesses, clothing, and book covers. Salt was in high demand and gathered in evaporation ponds - perhaps along North Sands. When a young lawyer, I lived near the remote settlement of Wee Jasper, centered on a hide making operation - a hard and demanding operation, which hasn't changed much in a thousand years.

This starts to build a picture of a town that needs plenty of areas to manage stock (at this stage hedgerows (a decent hedgerow might take centuries to develop) and temporary wooden hurdles were in use rather than extensive permanent fencing). A town needed lots of secure storage space.

Guards and weekly courts managed the temptation to take shortcuts with food, to compensate against errant stock, and to manage the moral care of the community. A gallows was established outside the Newborough Gate and was used by both civil and church courts.

Unlike most other European towns, Scarborough records suggest a degree of legal equality between people of different sex - women could bring action on their own behalf in the local courts.

Fishing

Fishing was a key element in the wealth of the town from earliest time. Fish were caught for local use (sales were restricted to the sands) but also preserved in salt for export.

Crops, Nuts and Fruit

Wheat, rye, and field peas were sown annually (sometimes a winter wheat crop was attempted at great risk). The fields were rotated and a third was left fallow each year, allowing stock to graze cut stubble, and fertilize the soil (corn was not available until the 16th century). In a bad year, about 160kg per acre of grain could be harvested for conversion to flour, requiring about 1500 acres under cultivation (one-third being left fallow for each year) - a not insignificant amount of land. For ease of plowing and the management of the communally managed sheep herd, this was spread across large contiguous spans of land cleared from the king's forests.

As with the communal care of flocks, most of the townsfolk would have been engaged in harvest activity - adults for reaping, older folk for tying the sheaves, and younger folk for gleaning grain lost during the reaping process. Reaping was attempted over a single day and sheaves were gathered on the same day to be stacked in purpose-built sheds to be wind dried. Gleaning of grain lost through the harvest process took place under close watch by the old and young over a couple of weeks. The stock was neither grain-fed nor permitted to graze on the stubble until gleaning was complete (coincidentally on the last day of the Fair). Theft was commonplace and kept the local town courts busy levying fines for attempted theft. It is estimated that state and church taxes took 10-15% of any private cropping.

In addition, the medieval diet included apples (fresh and cider), barley, nuts, and sea foods, such as shell fish. Again, these are more ancillary tasks than professions although, recently, in a village near my own farm, a chestnut farmer has renewed some of the old practices of building a mobile chestnut roast barrow and concocting delicious soups of that nut. A while back I planted a number of rows of English and Dutch medlars an almost indestructible fruit that remains hard until late winter and only then becomes palatable as it rots - a warm, indescribable chocolatey taste best appreciated when close to starvation.

Services

There were plenty of full time professions.

Salt was harvested (in later years under license from the North Sands) and used for preserving meat and fish and preserving leather.

Grain needs to be milled to be useful. We know of at least one water-driven mill. At this time, millstones were 2' to 7'. A modern 4.5-foot water-driven millstone at Peirce Creek (Washington) weighs in at 2,400lbs. It is possible that the Scarborough millstones were made of local stone and had a maximum throughput of 10 kg/hr to 30 kg/hr - although the smaller mills only worked as long as they could afford to use an ox and the larger was frequently stopping to rework the rope pulleys. Milling is dangerous and specialist work that requires a master millwright - with the stone rotating at about 100 revolutions a minute it is too easy to break the stone. We assume that there would be sufficient work in a poor year for 4 small mills (single yoked oxen) and 1 larger mill (water and rope driven) with town bakers producing 250-500 loaves each day. We have imagined the large mill as a stone building placed on the Damyot, well protected to discourage theft by human and beast. Cranes have been added to aid loading. Smaller mills have been scattered around outdoor circular stone oxen paths used to drive the stone at a much lower speed.

There were plenty of other service industries - some centered on the preservation of social and moral order.

Monks brought back stories of hospitals established by the universities in Constantinople. Towns made by-laws requiring excess food crops to be grown for land-less townsfolk.

Money lenders existed in most trade hubs, although at this stage there had been a concerted massacre of lenders in a number of Southern centers.

At this time, the Church (from York), the Crown courts, the local courts, monastic courts and the pre-Hanseatic trade courts were vying for control of certain areas of law - particular that relating to inheritance. The Church operated through inquiry - one example were the much hated Summoners who attempted to enforce moral codes but were well known for corrupt process. Crown and local courts operated though more open hearings.

As noted above, the moral care of the community was formally split between Church and Civil Courts - the Church focused on dissuading and punishing sexual misconduct - the civil courts were concerned with property consequences. However, it was not unusual for the mob to also take matters into their own hands by unruly gatherings demonstrating private behavior that caught the public attention, small and large.

At this time, the crusades had placed impossible burdens on the church dogma concerning an inviolate single marriage. Lots of men left wives to travel to the crusades. Many died or forged new lives in the Holy Lands leaving families back home abandoned and oftentimes beset with uncertainty for many years. Inroads started being made into the church-governed rules of marriage, with church courts (in York) commissioning inquiries into the possible death or the reasonable assumption of death. Closer to home, adultery, abandonment, violence, pre-marriage agreements and instances of bigamy drew attention. Defaulting parties were ordered to cease sexual activity and return to original spouses, and some were subject to court-ordered public shaming (which included being paraded through fairgrounds or tied to the town gallows for a day or two). The punishments do not seem to have had much effect, with some English communities adopting a "don't look, don't tell" approach to moral issues.

An economic slump a century later gives us a snapshot of Scarborough in its heyday "The number of bakers reduced from eight to four, all four drapers closed their shops, four butchers, ten weavers, and 11 tailors, all closed down and only half of the forty public houses remained in business." Perhaps we should take these numbers with a grain of salt - forty public houses would suggest 1 in every 5 houses was an inn. Still, as a trade hub, it is probable that a significant number of homes welcomed paying guests. The old meaning of 'Inn' is not necessarily associated with the conduct of a public bar selling alcohol.

Grass thatched roofs were prohibited within the town (although wood roof sheds and storage buildings might have been permitted - and the town may well have cycled through stages). At least 8 kilns (2 free-standing) have been found on Castle Road producing clay roofing tiles and the distinct Scarborough pottery.

Indication remains of rope working (along castle road), leather, and iron working - some associated with the port. Some of these industries were pursued well outside town. Associated woodworking activities (both general and specialized carpenters - such as wheelwrights, cartwrights, and joiners) no doubt also could be found alongside stone layers (and stone-thieves), tile layers and the various professions need to lay and maintain walls.

And there were doctors as well - barbers, herbists, apothecaries and the others.

Attempting to allocate the work across households gives us an interesting mix:

Occupation - Households - People - Count from 1000

Inn Keeper 35 157 842

Carpenter 30 135 707

Stonewright 20 90 617

Fishers 20 90 527

Tailers 11 49 478

Cartage 10 45 433

Weavers 10 45 388

Guards 10 45 343

Merchant 10 45 298

RopeMkr 8 36 262

Bakers 8 36 226

Millwright 6 27 199

Tiler 5 22 176

Salt Gatherer 5 22 154

Kilnwright 5 22 131

Shipwrights 5 22 109

Wheelwright 4 18 91

Butchers 4 18 73

Drapers 4 18 55

Leatherwkr 4 18 37

Ironworkers 2 9 28

Church 1 4 23

Moneylndrs 5 22 1

This does not include healers, bards, brewers, cooks, preservers, tin makers, rogues, and thieves. Nor does it take into account the incapacitated or those confined to the leper hospice.

A particular industry that deserves identification is the practice of thieving stone from older ruins. It is possible that older Saxon and Roman buildings were gradually recycled through the town, which relied on a good source of stones to found the lower foundations of buildings.

In all of this, I have been avoiding the monastic orders and outside-the-wall farming hides. One order was very active at this point in time and was probably providing a range of outward-looking services, including building, brewing, a scriptorium, a school, a hospice for returning or fleeing members from the palatine. Both rural dwellers and monks established farming operations outside Scarborough.

Index of posts in the series "Recreating the town of Scarborough, Yorkshire, 1264"

1: Geography

3. Crucks, Siles and Forks of Yorkshire

5. Surviving Medieval Structures

Comments